Seizing the Moment for Sustainable Water Governance in New Mexico

A Long History of Knowing—and Ignoring – For more than half a century, New Mexico has known that its water future is imperiled by persistent overuse, unsustainable pumping, and institutional failure. And for just as long, it has failed to act on that knowledge. Today, we face a narrowing window of opportunity to reverse that course. The 2023 Water Security Planning Act and other recommendations of the 2022 New Mexico Water Policy and Infrastructure Task Force offer a new legal and policy framework that could help New Mexico move beyond a legacy of neglect toward a model of proactive, inclusive, and science-based water governance.

Portales, Clovis, Cannon Air Force Base, and neighboring small towns face existential water shortages.

Ogallala Collapse Foretold—and Ignored – In 1968, the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer (OSE) published Technical Report 31, authored by hydrologist William Galloway. The report warned with unambiguous clarity that groundwater mining in eastern New Mexico was unsustainable and would ultimately collapse the agricultural base of the region. A 1999 OSE modeling report confirmed this trajectory of decline for the Ogallala Aquifer. Yet no policy shift followed.

Today, the communities of Portales, Clovis, Cannon Air Force Base, and neighboring small towns face existential water shortages, as the aquifer they solely depend upon is nearly forever depleted.

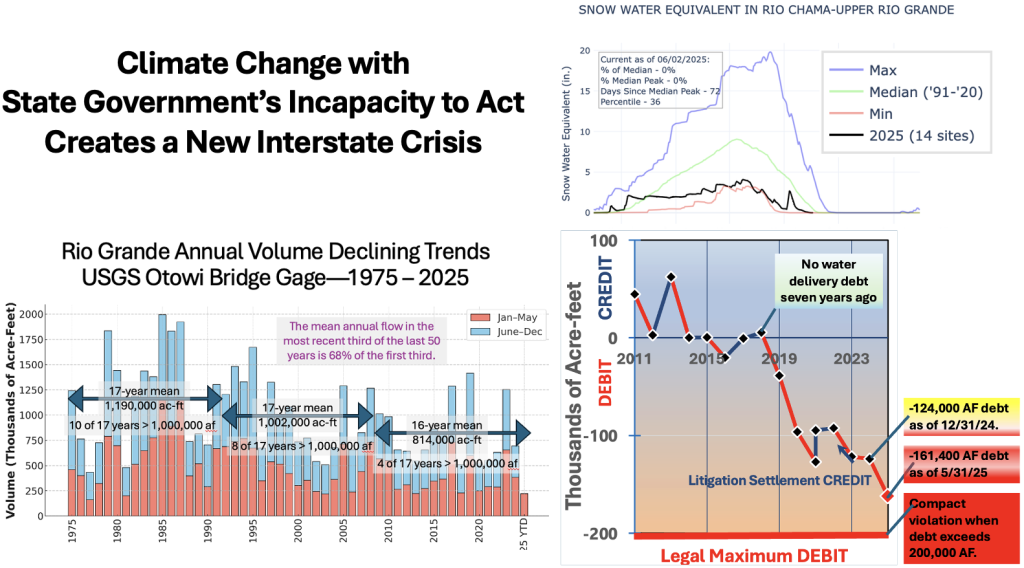

The Middle Rio Grande: A Crisis Denied – A parallel pattern of neglect has persisted in the Middle Rio Grande. Overuse and over-diversion of surface water, coupled with excessive groundwater pumping, have undermined both ecological health and legal obligations. This has triggered a new Rio Grande Compact compliance emergency centered on Middle Rio Grande water overuse. The cumulative effect of local water development coupled with state inaction and self-serving local water institutions has pushed the system to the brink. Yet, there remains no unified plan or political will to rein in the overuse or enforce sustainable limits.

State Engineer General Counsel Nat Chakeres recently announced meaningful water policy changes are forthcoming. His presentation covering both the problem and the solution is the best and most accessible I have seen. He admitted it may be too late.

The Governor’s FY26 budget recommendation included dedicated staff and office space for the State Engineer to begin essential regulation of Middle Rio Grande overuse. It died by inaction of the House Appropriations and Finance Committee.

Plans Unheeded: Policy Paralysis – In 2002, the nonprofit 1000 Friends of New Mexico published Taking Charge of Our Water Destiny, a sweeping and thoughtful roadmap for comprehensive water reform. The report called for state leadership, regional empowerment, and public participation in water planning. It urged the use of science, transparency, and collaboration as the foundation of decision-making.

Two decades later, those recommendations remain strikingly relevant—and largely unfulfilled. Once again, knowledge was not the problem; the failure was in the doing.

Once again, knowledge was not the problem; the failure was in the doing.

Public Welfare Standard: Dormant by Design – The consequences of that failure are now visible statewide: rivers drying, aquifers collapsing, and legal obligations nearing breach. Yet even now, decision-makers struggle to apply the tools that already exist. One of the most powerful is the statutory requirement that water rights transactions be consistent with the public welfare of the state. Though this criterion was added to New Mexico law in the 1980s, it has never been defined or interpreted to reflect today’s hydrologic, ecological, or societal realities.

As legal scholar Susanne Dooley Hoffman wrote in 1997, the public welfare standard is a dormant authority—a tool requiring additional legislative definition to ensure that private water use aligns with the broader needs of communities, ecosystems, and future generations. These essential and equitable needs were described by Mr. Chakares as valid claims “that are not going away.”

Ms. Hoffman-Dooley argued that the Legislature’s designation of “the public welfare of the State” as one of three statutory criteria for the State Engineer’s discretionary approvals without defining it is unconstitutional. Almost three decades later, we now await a New Mexico Supreme Count decision related to an illegal lease of a previously dormant Pecos River water right in the Intrepid case by a State Engineer that abused the public welfare of the state criterion. The ISC protested the application that the State Engineer later approved because it was so obviously counter to the public interest and dollars spent to comply with the Pecos River Compact. The State Engineer fired the ISC Director. In this case, the ISC persisted, and will be vindicated in the forthcoming decision.

Here again, the problem is not in the knowing, but in the failure to act.

Sufficient understanding and the political will to confront New Mexico’s existential water crisis does not yet exist in the Governor’s office or the Legislature.

Leadership Vacuum: Executive and Legislative Inaction – This long pattern of neglect—in science, in policy, and in law—must end. Yet the failure is not only administrative. It is also legislative. During the interim between sessions, legislative committees often hold hearings that illuminate the gravity of New Mexico’s water problems. These hearings gather testimony, generate interest, and highlight urgent needs. But rarely—if ever—do they result in committee-sponsored water policy reform legislation. In the 2025 session, the Legislature essentially ignored water resources sustainability altogether.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s office provided no water resources sustainability leadership, leaving state water institutions with a crippling lack of permission to take the bold steps required. Inaction makes it clear that sufficient understanding and the political will to confront New Mexico’s existential water crisis does not yet exist in the Governor’s office or the Legislature.

Effective water governance cannot flourish without transparency, accountability, and public inclusion.

The ISC Restricts Participation – Interstate Stream Commission’s policies are problematic examples. In March 2025, the ISC staff revealed its intended process for the Commission to promulgate regional water planning rules. The announced process would limit technical and expert testimony to only those experts selected by the ISC staff, not withstanding due process guarantees of law. Another example: the ISC’s public comment policy requires a written submission 72 hours in advance with no opportunities for public engagement at ISC public meetings.

At a time when broad civic engagement is critical, the Commission’s approach is misaligned with the scale and urgency of the water supply challenges facing the state. Effective water governance cannot flourish without transparency, deliberation of policy decisions in public, accountability, public inclusion, and yes, due process.

A Path Forward: The Promise of Polycentric Governance – The Water Security Planning Act of 2023 provides a way forward. For the first time, it mandates the creation of regional water planning councils empowered by statute and supported by state resources. These councils represent a shift toward polycentric governance: a model that recognizes the diversity of New Mexico’s water challenges and enables regionally informed solutions within a statewide framework. But that potential will not be realized if state institutions cling to the command-and-control habits of the past.

We have the legal foundation and the scientific understanding. What remains is the political courage to act.

What Must Change: Vision, Function, and Courage – To succeed, the water planning program must be grounded in a clear vision: one that distinguishes the appropriate roles of state and regional actors, prioritizes transparency and public participation, and builds from the ground up. Funding must follow function. Councils must have the means to organize themselves, evaluate and understand water data, and propose actions suited to their unique conditions. And the State Engineer and Interstate Stream Commission must lead by enabling—not overriding—local and regional responsibility.

No More Waiting – New Mexico has waited far too long to confront its water realities. But today, we have sufficient legal foundation, scientific understanding, and the community will. We lack the political courage of our elected and appointed leaders to lead and share power to confront our water crisis. To date, they collectively lack political will. We, and they, must change that.

Let’s take charge of our water destiny, together.

July 10, 2025 @ 9:34 am

The Office of the State Engineer established a policy in 1956 for the management of the High Plains Aquifer (formerly known as the Ogallala) and the Estancia Basin that designated a 40-year operational timeframe for the aquifer. This approach treated the aquifer as a finite resource, with no provisions for long-term sustainability. The 40-year period was determined to facilitate agricultural financing, enabling banks to provide loans to farmers. Additionally, farmers were granted tax credits to offset increased pumping costs as groundwater levels fell. Ultimately, the region made a strategic decision to extract groundwater primarily for the production of cattle feed.

In response to the long-term decline of groundwater resources, the Ute pipeline, now under construction, marks a significant shift in regional water management. Designed to deliver surface water from the Ute Reservoir, this pipeline aims to supply Clovis and several surrounding small communities. By securing an alternative water source, these communities hope to reduce their dependence on the rapidly depleting aquifers, ensuring greater reliability for future generations and supporting residential needs.

June 17, 2025 @ 4:51 pm

Norm:

There is nothing existential about the impending doom of Eastern New Mexico. We have recently valued a 1000 acre foot block of water rights in Clovis at $36,000 per afcu.

June 18, 2025 @ 6:30 am

Bill:

Buyer beware. The Ogallala is almost drained of water. That paper water right your firm is marketing for sale, the legal right that allows water to be consumed, won’t wet your whistle when the well runs dry.