A Smarter Path Forward for New Mexico

The Interstate Stream Commission (ISC) staff’s proposed rule to implement the 2023 Water Security Planning Act (WSPA) is structurally flawed, legally overreaching, and misaligned with the law’s purpose. The WSPA was enacted to support decentralized, data-informed, and science-based water security planning across New Mexico. Instead, the proposed rule concentrates inappropriate, poorly defined authority in the hands of ISC staff.

It presumes that internal staff policy decisions—many of which constrain regional initiative—should be embedded in rule, without ever being considered by the Commission. It contradicts the Act’s clear delegation of planning responsibilities to regional councils. It even instructs councils to proceed with planning whether or not data are lacking, undermining the scientific integrity that the WSPA mandates.

Despite taking two years to prepare, the proposed rule is vague, contradictory, and fails to meet drafting standards for state rules. The staff-proposed rule lacks clarity, misinterprets statutory intent, and fails to learn important lessons from failures of past ISC-directed regional water planning in New Mexico that used imaginary information.

This article outlines core flaws in the proposed rule and proposes a smarter path forward: pause the rulemaking, adopt interim guidelines that fund and support regional initiative, and return to the formal rule process only after meaningful engagement, learning, and course correction—grounded in statute and committed to decentralization. The Water Advocates described the flaws and pointed out the better way in public comments offered for the Commission’s consideration.

The proposed rule substitutes staff discretion for Commission-level decisions and undermines both scientific integrity and the decentralized authority that the Act assigns to regional councils.

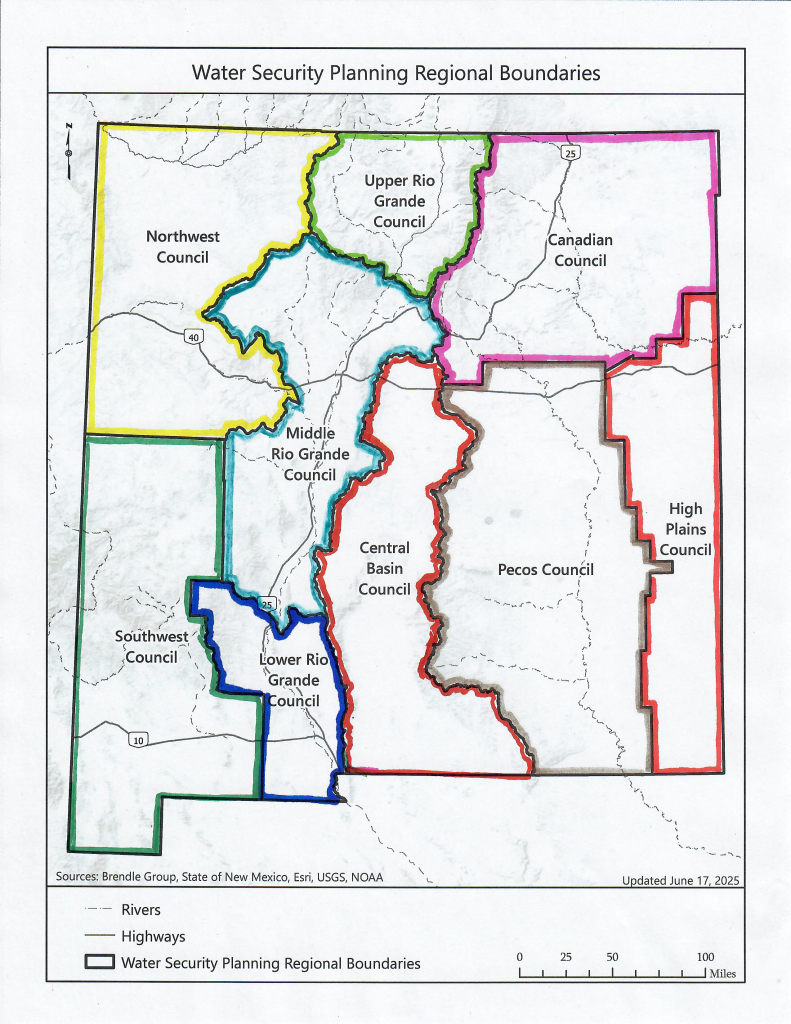

The Water Advocates Support the ISC’s definition of the regional water planning council areas, as shown. The boundaries make sense and are well examined by ISC staff and explained.

Centralized Control Where Regional Responsibility Is Required

Centralized Control Where Regional Responsibility Is Required

At it’s heart, the WSPA is a commitment to decentralized planning: regional councils are charged with developing water security plans, while the state is to support councils’ work by providing technical and financial support with clear content and approval criteria. The Act requires the Commission to define council composition, support plan development, and approve plans based on established rules. Nowhere does it authorize the ISC staff to initiate the formation of regional councils or approve each council’s membership.

Yet the proposed rule does exactly that. Rule 10 A.(1) asserts that NMISC staff will invite government entities to select representatives and will convene the initial meeting of each council. This is a fundamental overreach. The WSPA assigns the duty of plan development to regional councils themselves. The Commission’s statutory role is to establish composition standards—not to centrally initiate, schedule, or approve when and how councils form. Rule 10(C) makes this overreach worse by stating that self-organized councils must be “confirmed by NMISC staff”—but confirmed according to what criteria? The rule provides no standards, thresholds, or procedural guidance.

The problem extends further. Staff would be granted authority to review and approve council composition when vacancies occur, with no defined criteria, timeline, or appeal process. Rule 12 empowers staff to substitute non-voting members for voting members if a “qualified or willing” representative cannot be identified—but fails to define either term or require Commission oversight. These and other provisions allow staff to shape council membership and authority with excessive discretion, undermining the WSPA’s statutory structure by assigning staff roles the law reserves for regional councils or the Commission itself.

Many regional leaders lack only a legitimate framework and resourcing strategy that honors their statutory roles and the decentralization mandate.

Failure to Meet Statutory Requirements

The WSPA includes several specific rulemaking mandates that the proposed rule fails to fulfill. Two are particularly critical:

- Section 8(C)(1)(c) requires rules that establish a procedure for regional entities to develop and notify the Commission of regional public welfare concerns.

- Section 8(C)(1)(e) requires rules that establish a procedure for regional entities to consider public welfare values and the needs of future generations.

The proposed rule establishes no procedure for Councils to raise such concerns to the Commission, and no structured process for evaluating those concerns in regional planning. These omissions are direct failures to implement core provisions of the statute.

Integrity of Planning

Scientific integrity is another area where the proposed rule falls short. The rule language evades the statute’s clear mandate that the Commission must both provide the best information and ensure it is used with scientific integrity.

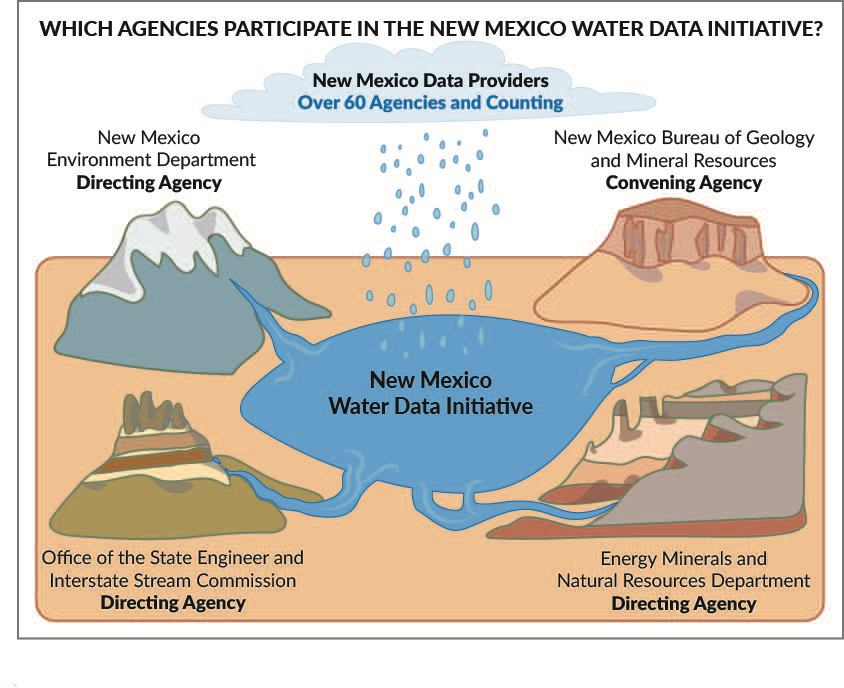

The Water Security Planning Act plainly requires the Commission to ensure “the best science, data, and models relating to water resource planning are available to the regional water planning [councils] and are used with scientific integrity and adherence to principles of honesty, objectivity, transparency, and professionalism.” It further requires the ISC to carry out this responsibility in collaboration with the Bureau of Geology and to do so through Bureau’s New Mexico Water Data Initiative.

The proposed rule omits any reference to this specific ISC duty and makes no mention of the Water Data Act platform. The rule instead offers only vague references to “assistance with accessing” data. Worse still, the proposed rule says, “Councils may not delay the development of or updates to a plan due to lack of data.”

Water planning without water data is not water planning with integrity. The rule drafters may have had a more complex idea in mind, but the language is too terse to communicate the circumstances where Councils may not delay due to lack of data.

Nothing good came from the ISC’s 2018 regional water planning updates that ISC asked be completed without real data. New Mexico has seen the costs of ISC’s turning its back on scientific and decision integrity during the Gila River Diversion process from 2004 through 2020. The 2023 Water Security Planning Act explicitly corrects those problems, among its many changes. The proposed rule doesn’t operationalize these reforms.

New Mexico has seen the damage and waste caused by ISC politicized water planning that flaunted scientific integrity. ISC pursued a 4th iteration of the clearly infeasible Gila River Diversion project from 2004 until they finally stopped work in 2020. ISC modeling, public meetings, and reporting were deliberately misleading, professionally indefensible, and extremely wasteful, costing at least $16 million in federal funds and diverting many years of ISC’s limited staff resources to a boondoggle. The ISC even manipulated the Southwest New Mexico Regional Water Plan to prioritize the infeasible diversion project, causing that endeavor to be wasted, too. The Gila River Diversion Project case is the reason the 2023 Water Security Planning Act includes the bolded sentence quoted above.

Schedule

ISC staff presented this slide to the Commission 0n June 18, 2025. The ISC planning chief’s remarks indicated staff wants to deny six of the nine regions the opportunity to participate in state funded regional water planning until 2032 or after. The staff rule is silent on the schedule, delaying that discussion for a future Commission proceeding.

A Better Path Forward: Pause, Activate, Align

Given these failings, the Commission should immediately pause its current rulemaking process. The draft rule as written cannot be the foundation for a planning program that meets legal standards, inspires public trust, empowers regions to confront their water challenges, or expands the number of minds engaged in New Mexico’s water resources problem-solving.

Instead, the Commission should adopt an interim approach using its statutory authority to fund regional activities. The Commission can and should adopt simple, short-form interim guidelines (not a full rule) to activate regional initiative through flexible early-stage grants. These guidelines would:

- Allow grants to eligible fiscal agents for existing or new groups formed by regional initiative to carry out early regional organizing work;

- Support activities such as convening intergovernmental forums, convening inclusive regional meetings, identifying and engaging local stakeholders, initiating council formation consistent with WSPA-mandated composition rules, or conducting preliminary needs assessments;

- Require transparency and accountability through basic reporting

- Allow regions to design their own path toward formal council establishment and plan development.

This approach enables planning regions to take initiative in a manner tailored to local realities—without entrenching a rigid, staff-controlled structure that predetermines the shape of regional councils or the methods of engagement. It also allows state support to flow quickly and equitably across the state, even as the formal rulemaking process is paused.

Importantly, many regional and tribal entities already possess the relationships, capacity, and readiness to engage in meaningful planning. What they lack is a legitimate framework and resourcing strategy that honors their statutory role.

The Commission should pause the rule, activate regional initiative through interim guidelines, and return to rulemaking only after real public input and on-the-ground experience.

Re-Centering the Commission’s Role

Perhaps most importantly, this alternative approach would restore the proper institutional balance between the Commission and its staff. Under the WSPA, the nine-member Interstate Stream Commission—not its staff—is the statutory deliberative and policy-making body.

The July 17, 2025, Commission meeting revealed that staff had already made key structural and policy decisions without presenting them to the Commission for public deliberation or approval. Commissioners had not been briefed on decision options. Staff had not analyzed alternatives. Staff withheld critical information from public meetings and embedded its staff-centric and centralized control policy choices in the draft rule.

Moreover, the staff-led public engagement process was inadequate. It relied heavily on dot-voting at open houses and through the mainstreamnm.org platform, which limited public learning and discouraged narrative input. While the Water Advocates and others submitted detailed written critiques, staff failed to present these to the Commission in a structured or comprehensive form. At no point did ISC staff convene a public forum where stakeholders could learn from one another or engage with subject matter experts. The process appeared designed to generate superficial evidence of consensus on simple points rather than support meaningful public input and policy guidance.

By pausing rulemaking and adopting interim guidelines, the Commission can reclaim its deliberative policymaking role and publicly structure the development of a planning program with a set of rules that meets both the letter and spirit of the WSPA.

Conclusion

The ISC staff’s proposed rule gets the Water Security Planning Act wrong in both structure and intent. It centralizes what the law seeks to decentralize. It assigns staff discretionary authority where the law assigns Commission oversight. And it fails to implement key statutory provisions that are essential to meaningful, lawful planning.

A better path is available: pause the rulemaking. Activate regional initiative through interim guidelines providing for flexible grants. Re-center the Commission’s policymaking authority. And only after sufficient on-the-ground engagement, regional mobilization, and public input, return to the rulemaking process with a foundation grounded in statute, experience, and trust. That’s how New Mexico can begin to build true water security community by community, region by region, starting now.