The Middle Rio Grande’s 2025 River Water Supply Has Collapsed

A Sobering Conversation

On Friday, August 1, a kind and knowledgeable hydrologist at the Bureau of Reclamation’s Albuquerque office responded to my questions about the Middle Rio Grande’s river water supply and our year-to-date Compact deliveries to Elephant Butte. The answers were sobering.

The Future Has Arrived Early

It’s time to stop talking about New Mexico’s projected 25% reduction in renewable surface and groundwater supply by 2070. That number, from the widely cited 2021 report by the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, now understates our crisis. The 2025 shortfall in river water supply is more than 50%.

The riverbed through metro Albuquerque is dry. The Bureau of Reclamation’s San Juan–Chama Project, which imports water from the Colorado River Basin, hit a record-low allocation in 2025. This year’s water for project contractors is down 69% from a full supply. That’s a massive shortfall for the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, which receives about half the water, and the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District , which receives about a quarter.

Data show the decline in river flows over the last 50 years, as illustrated in the chart below that I prepared in early June. The drone photo below the chart shows the river channel at the US380 highway bridge near San Antonio in August 2022, a relatively dry year. The river there had water then and the fields are green. This year, the fields may be green but due to rain and groundwater pumping. The river is dry.

Compact Risk Is Flashing Red

At the May 15 Water Advocates workshop*, State Engineer General Counsel Nat Chakeres stated his belief that the Middle Rio Grande would avoid a Rio Grande Compact violation this year because the water delivery obligation to Elephant Butte is so low. I concur.

But unless the unusual 2025 monsoon delivers a lot more water across the dry watersheds to the river, the Middle Rio Grande’s accrued water delivery debt will rise to roughly 160,000 acre-feet—using up half of New Mexico’s remaining margin. That margin is our buffer before high-stakes interstate litigation returns.

If we exceed the 200,000 acre-foot legal cap on cumulative water delivery debt, we will once again face Texas in the U.S. Supreme Court—this time in another risky, high stakes case that will cost over $100 million and a decade or more to defend. The still ongoing 2013 lawsuit filed by Texas and joined by the United States over New Mexico groundwater pumping in the Lower Rio Grande cost more and is taking longer.

Texas’ formal attempt to bring Middle Rio Grande under deliveries into the ongoing Lower Rio Grande litigation failed, because we remain in compliance, that is, our water delivery debt doesn’t exceed the cap. The Compact creates a clear dividing line that isolates the Middle Rio Grande from the Lower Rio Grande, but only as long as the Middle Rio Grande remains in compliance.

What Must Be Done

We must acknowledge that our renewable water supply is shrinking now—not decades from now. And we must act accordingly. Either we take strong action to comply with the Compact, or we will be forced to devote our state’s water agencies to the enormous task of defending a new Supreme Court case—this time involving water for half of New Mexico’s economy and population. And we will be forced to comply, but with less leeway and discretion.

*Visit the “Past Events” tab at nmwateradvocates.org to access the May 15 workshop recording and slides.

Technical Notes:

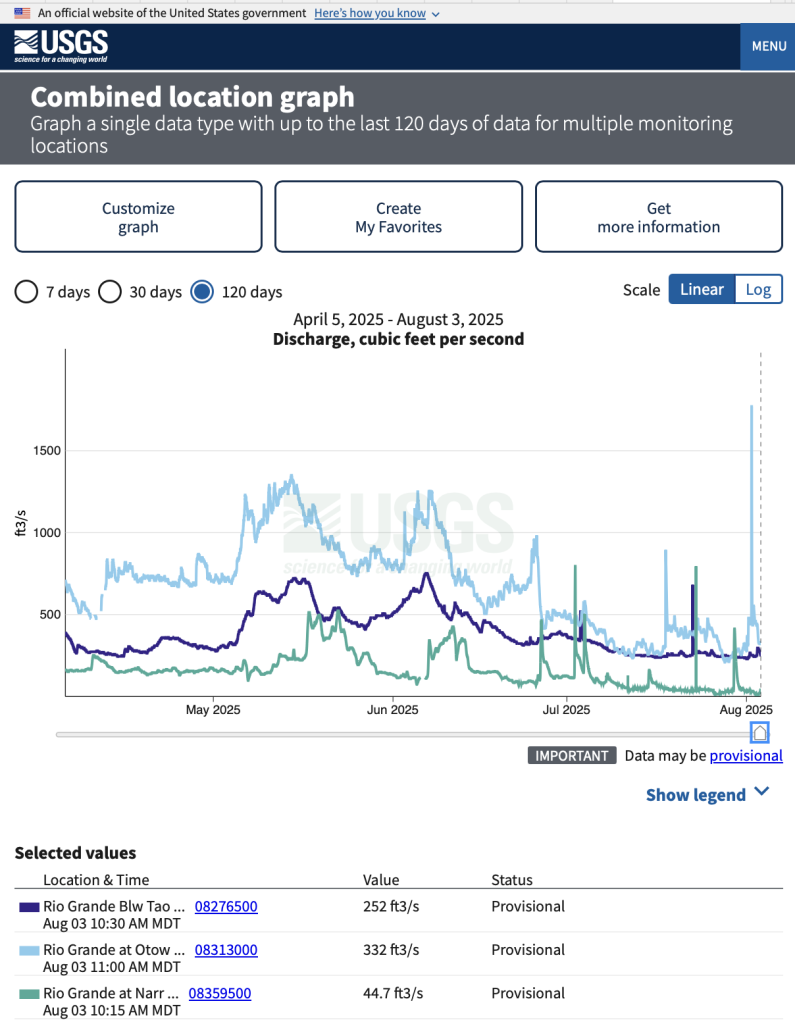

This U.S Geological Survey Chart

The light blue trace in the chart below is from the U. S. Geological Survey’s river streamflow gage at the Otowi Bridge on the Los Alamos highway. It measures Rio Grande Compact inflows to the Middle Rio Grande. San Juan-Chama water volumes are subtracted from the gage reading, which is also adjusted for changes in upstream reservoir native water storage.

The green trace measures the outflow from the Middle Rio Grande at the Narrows within Elephant Butte Reservoir, where the river is flowing in an accessible channel many miles upstream of where the stored water pool has retreated. This is a temporary gage and is useful. The Rio Grande Compact actual water delivery is calculated as the change in storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir plus the release through Elephant Butte Dam.

The dark blue trace shows the flow of the Rio Grande downstream from the Rio Pueblo de Taos. It measures Colorado’s stateline deliveries, tributary inflows and the flows including the Red River and the Rio Pueblo de Taos, and large springs in the upper Rio Grande Gorge. Most of the additional water measured at the Otowi gage (light blue) comes from the Rio Chama, the Rio Embudo, and inflows minus diversions upstream from Espanola.

Comparison of the light blue and green traces shows very little of the inflow to the Middle Rio Grande has made it through. The compact requirement is 57% on an annual basis.

Current Data from Reclamation

Reclamation’s hydrologist said the Otowi gage flows include delivery of 33,884 acre-feet of San Juan-Chama project water in 2025 year-to-date. MRGCD has used essentially all of its allocation.

Federal agencies stored 32,668 acre-feet of native Rio Grande water under conditions when the Compact does not permit storage to guarantee water to meet the “prior and paramount” irrigation requirements for certain Pueblo lands. Of that total, 2,100 acre-feet has been released as of the end of July. The current rate of release is 40 cfs. It has been as high as 60 cfs. All remaining water will be released for delivery to Elephant Butte after the end of the irrigation season. Ir’s rare that prior and paramount water is used because normally the minimum flow of the river is enough. A substantial amount may remain, or not, depending on the monsoon.

The Upper Rio Grande Water Accounting Model shows the Middle Rio Grande’s year-to-date underdelivery of water to Elephant Butte as of the end of July is – 39,000 acre-feet.