What Happened to the Flood? The Middle Rio Grande Ate It!

October’s Big Storm Helped the River But the Middle Rio Grande Depleted 40% of the Lower Rio Grande’s Share

An intense rainstorm centered on the San Juan River mountain headwaters spilled over into the headwaters of the Rio Grande, sending a surge of mountain runoff into the San Luis Valley. This is the storm that flooded Pagosa Springs. The October 14 Alamosa Citizen story headline on the flood was followed by the reporter’s understanding of routine Colorado water management in the subtitle, “Now it’s time to measure and account for the extra water in management of the Rio Grande Compact.”

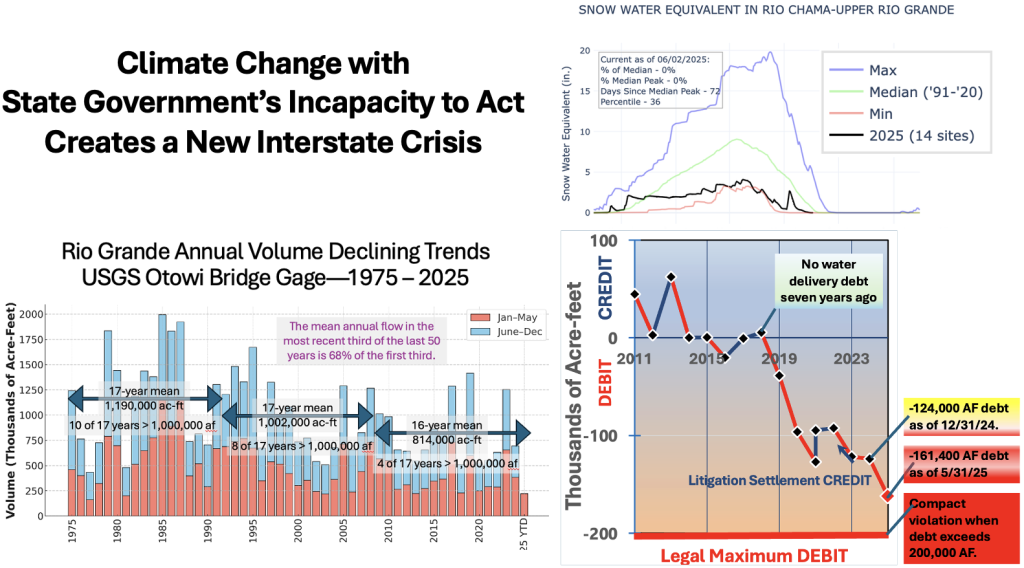

The Rio Grande at the Del Norte gage peaked at 7,000 cubic feet per second—a very high flow for autumn. The Colorado Division of Water Resources contemporaneously estimated 20,000 to 25,000 acre-feet entered the San Luis Valley in Colorado, and reported that 15,000 acre-feet was diverted into the Valley’s canals. Colorado’s Rio Grande Division Engineer, Pat McDermott, told the Rio Grande Basin Roundtable that the Middle Rio Grande might see roughly 5,000 acre-feet of this water, but that it would likely not extend as far south as Elephant Butte Reservoir. The Rio Grande benefit in New Mexico actually was much larger but he was right about Elephant Butte.

Because the Rio Grande Compact divides the river’s flow among Colorado, the upper, middle and lower Rio Grande in New Mexico, and the Lower Rio Grande in Texas, how each state measures and manages water determines whether its downstream obligations are met.

The irrigation season in Colorado and New Mexico ended November 1. Colorado flows increased as a result but are tapering down. Deliveries into Elephant Butte are now slowly increasing, but didn’t benefit from the Colorado flood. The contrast between Colorado’s prompt accounting and New Mexico’s limited conveyance is striking.

A Growing Water-Delivery Debt

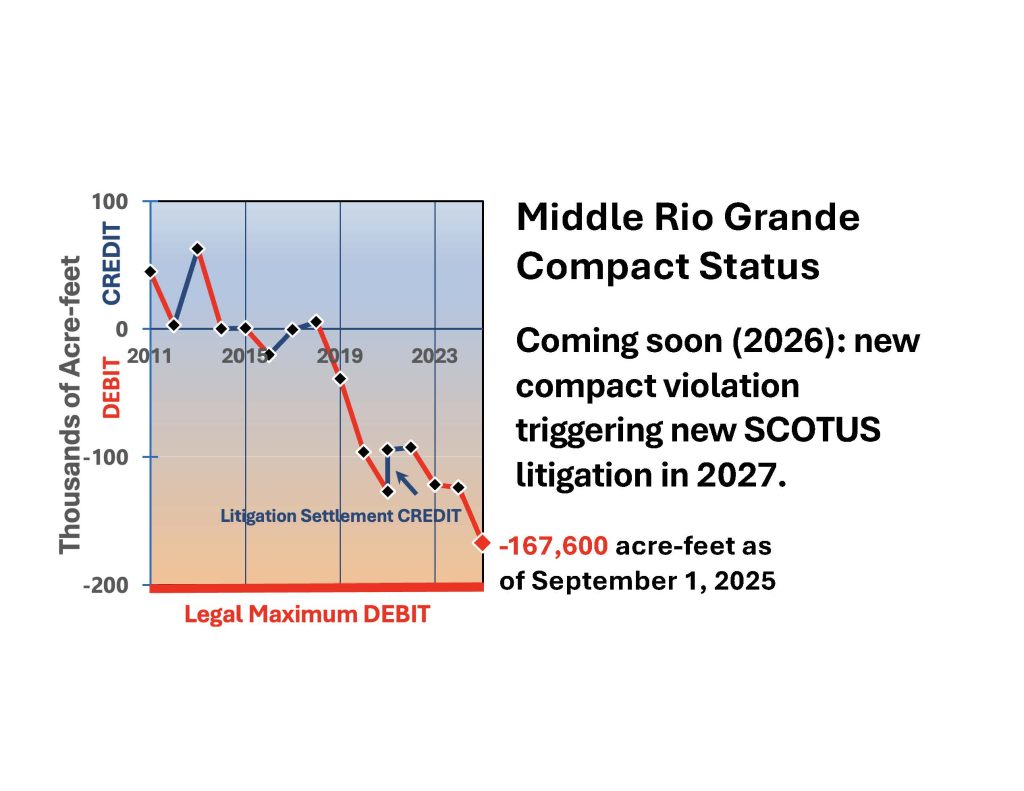

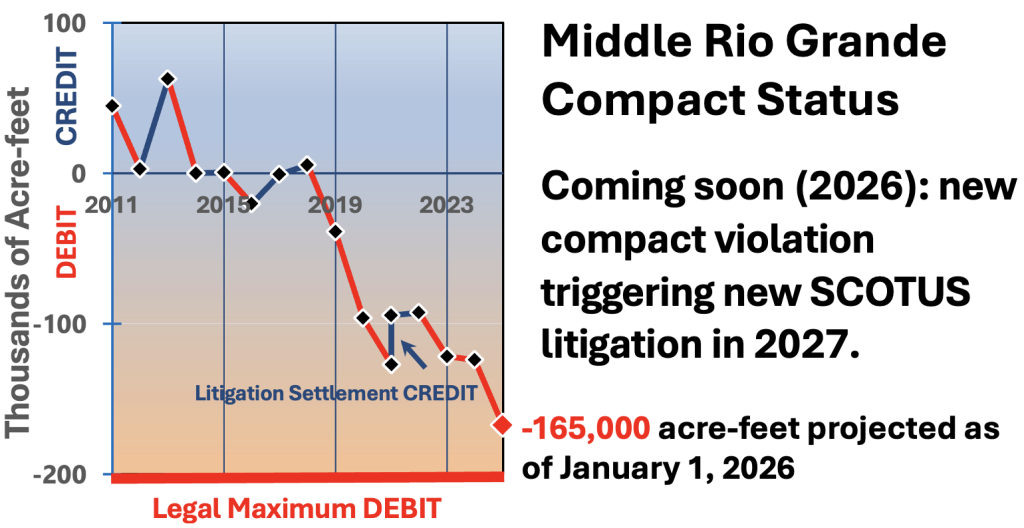

The Middle Rio Grande entered the year 124,000 acre-feet behind in its accrued annual water deliveries to Elephant Butte Reservoir. Throughout the year, that debt has inexorably grown due to the complete failure of this year’s spring runoff and the Middle Rio Grande’s excessive depletions over the last 15 years. New Mexico does not manage the Middle Valley’s groundwater pumping, which accelerated due to lack of river water, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s diverting more than New Mexico’s share, and poor channel conveyance.

Neither the State Engineer nor the Interstate Stream Commission have publicly discussed this year’s growing debt. Neither has emphasized New Mexico’s serious risk of a new violation of the Rio Grande Compact due to the Middle Rio Grande’s chronic taking of the Lower Rio Grande’s share, year after year.

I decided to calculate what happened on the Rio Grande in New Mexico from the storm. I used online river and reservoir gage data from October 12 through November 9, the last day for which a complete data set is available online. My calculations show that between those dates, 40,900 acre-feet of water flowed under the highway bridge to Los Alamos as measured at the Otowi Bridge gage. Colorado state-line water deliveries were about 60 percent; the other 40 percent came from New Mexico springs and tributaries. The Lower Rio Grande’s share of that, which is the same thing as the Middle Rio Grande’s delivery obligation, was 23,300 acre-feet.

Elephant Butte’s storage increased only 14,000 acre-feet and releases were 100 acre-feet, creating an actual water delivery during this period of 14,100 acre-feet. The result: this a deficit of 9,200 acre-feet over this 29-day period was added to New Mexico’s 2025 debit. Roughly 40 percent of the water that should have reached the reservoir disappeared within the Middle Valley.

Some unknown combination of Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District diversions, increased groundwater pumping that induces recharge from the river, and the poor water-conveyance condition of the river channel upstream from and into the nearly dry Elephant Butte Reservoir absorbed or intercepted much of the flow. This is why so little of the high flows reached Elephant Butte, leaving New Mexico much worse off with regard to its Compact obligations.

Why I’m Tracking Deliveries Monthly

The Water Advocates for several years has urged the Interstate Stream Commission staff to begin paying public attention to water deliveries through the Middle Rio Grande each month and forecasting the year-end results. Sure there are uncertainties and unknowns, but both tracking intra-year progress and forecasting the year-end results are an essential first step to recognizing and managing this serious problem.

The State can’t manage what the State doesn’t measure—and that includes contemporaneous annual compliance as a year progresses. Water delivery debt has grown significantly during 2025, without any Interstate Stream Commission acknowledgement of that fact. Both the facts and state agency silence should alarm the Legislature and the public.

My independent review of this year’s Compact deliveries began this summer. I requested data at the end of each recent month from the Bureau of Reclamation’s engineer who operates the official Rio Grande water accounting model. Last month he discovered a problem with the initial condition for the 2025 accounting. We both made bad estimates because Reclamation’s Elephant Butte Reservoir instrumentation, which measures the reservoir’s water-surface elevation and determines its storage volume, became stuck. I misunderstood how the model accounts for federal storage of New Mexico water in Rio Chama reservoirs to ensure the six Middle Rio Grande Pueblos’ Prior and Paramount water rights have a full supply. The release of unused prior and paramount water between now and the end of the year should materially improve net Compact deliveries over the remainder of the year because it was properly accounted when it was stored.

The Outlook

I project the year will end with an annual 2025 Middle Rio Grande water-delivery debt of about 26,000 acre-feet and an accrued water debt of about 150,000 acre-feet. If so, that may give us two years to avoid a Compact violation rather than only one. We must use this time to stop and reverse the current trend, prevent the violation that continued inaction will cause, and begin working our way out of Compact debt. Any accrued water debt above about 50,000 acre-feet effectively prevents Middle Rio Grande water from being stored upstream in Rio Chama reservoirs.

A public agency can’t deal with a complex problem that impacts the public unless and until the agency names the problem and describes it. A problem can’t be managed if progress toward the desired outcome is not measured. The State Engineer’s job is to comply with the Compact. The ISC’s job is to gather accurate information, professional analysis, and make it publicly available. Both have the duty to communicate openly and promptly.

I speculate this crisis is getting the silent treatment by both state agencies because they don’t have the Governor’s consent to confront it. Dealing with this compact emergency is not in the Governor’s 50-Year Water Action Plan. Neither is water planning. If we have to wait for a new Governor to attend to New Mexico’s water emergency, it may not be in time to prevent a brand new Texas v. New Mexico case before the US Supreme Court. Failing to take serious action now is another step toward the huge risks and costs of the litigation that will follow a violation. That’s a poor legacy for everyone involved.

New Mexico needs transparent water management to prevent the looming Compact violation. It needs funding. It needs it now.

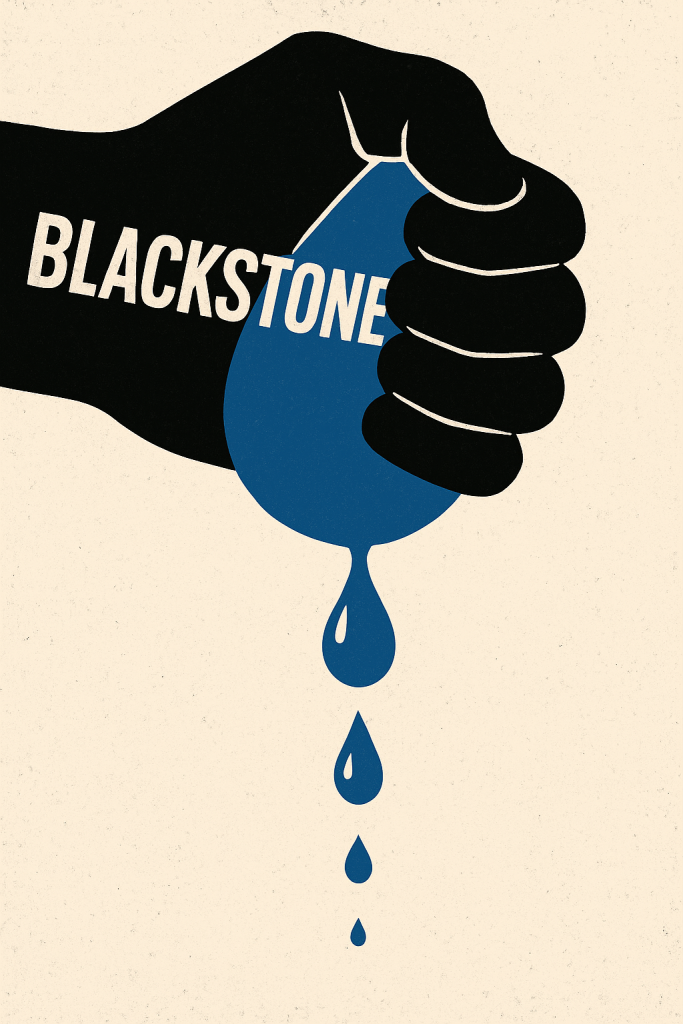

Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm, has its own long list of controversies—several of which implicate fundamental rights and public trust.

Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm, has its own long list of controversies—several of which implicate fundamental rights and public trust.